Vaccination Abomination, or Vaccination Upholds

the Nation?

John Pitcairn and the Struggle Against Compulsory Vaccination

Cairn

King

Introduction

to the National Anti-vaccination Movement

New Church Anti-vaccinationism

Before the Crisis

Struggle in Bryn Athyn: Vaccination Strikes

Home

John Pitcairn and the National Anti-vaccination Movement

Conclusion

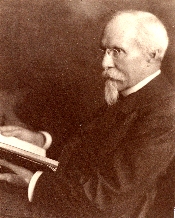

John Pitcairn, president of the Anti-Vaccination League of America from 1906–1916. Photo: John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives. Click on image for a larger version.

When an incidence of smallpox struck Bryn Athyn in 1906, this small religious community was thrust into the swirling national debate over compulsory vaccination for children. Members of the Bryn Athyn community who opposed vaccination found themselves faced with the dilemma of whether to succumb to vaccination or risk civil disobedience against the overwhelming superiority of civil authority. Like others in Bryn Athyn, John Pitcairn had long opposed vaccination for medical, political, and spiritual reasons. Now that the issue had reached Bryn Athyn, Pitcairn committed himself to the battle against compulsory vaccination. At the insistence of Bishop William Frederic Pendleton, Pitcairn resisted turning Bryn Athyn into a battlefield over the issue. Instead, Pitcairn turned his attention to the national scene, realizing that he could make more of a difference on this level by joining the small, but vocal national anti-vaccination movement. Much like Pitcairn, the leaders within this movement argued that compulsory vaccination posed both health risks and a threat to individual freedom. Rather than risking damage to his beloved Bryn Athyn, Pitcairn played a key supporting role by joining with like-minded individuals and organizations in the national struggle to change compulsory vaccination legislation.

Introduction to the National Anti-vaccination Movement top

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a movement known as "progressivism" dominated the political climate of the United States. Progressives believed that they could and should support public policies aimed at solving social problems. One project of the progressives that attracted substantial criticism was the attempt to eradicate smallpox by mandating that all parents have their children vaccinated as a requirement to enter school. Smallpox vaccination had existed prior to the twentieth century and had often proven itself dangerous but fairly successful in preventing the dreaded disease. In the late eighteenth century, Edward Jenner discovered that exposing a healthy person to cowpox, a relatively minor disease closely related to smallpox, by means of a cut in the arm, tended to make this "vaccinated" person resistant to smallpox. Throughout the nineteenth century resistance to smallpox was created by this method of arm to arm or cut to cut vaccination. While a significant chance existed that, as a result of this practice, the vaccinated person could contract serious or deadly secondary diseases, smallpox was so horrific that many people took the risk and opted for vaccination. By the late nineteenth century injection of vaccination by hypodermic needles eliminated many of the risks associated with arm to arm vaccination. This change would have resulted in a lessening of opposition to vaccination but for a significant factor. Smallpox, or variola major, suddenly died out, giving way to a far less dangerous strain of smallpox, variola minor.1 From this point on, according to historian Robert Johnston, "the twentieth century [as opposed to the nineteenth] . . . saw a much safer vaccine chasing after a much less dangerous disease."2 The disease barely claimed a fatality after this time, and by the twentieth century, while vaccination became safer, opposition to it continued to grow as more and more people perceived it as an unnecessary risk given the metamorphosis of smallpox from a killer to merely a nuisance. Coinciding with the decreasing fear of smallpox came laws requiring vaccination. Many states passed what Colgrove correctly refers to as "a loose patchwork of state and local laws,"3 that the Supreme Court of the United States ultimately upheld in the 1905 ruling of Jacobson v. Massachusetts. After this ruling anti-vaccinationists waged a battle to gain public support aimed at changing compulsory vaccination legislation rather than fighting it in the courts.4

The prominent anti-vaccinationists in this period, dating roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s, came from various backgrounds and were connected by their shared objection to compulsory vaccination. Collectively they saw it as a potentially hazardous medical procedure, and they believed that the compulsory element smacked of tyranny and subversion of individual freedom. They fought a propaganda war by means of rallies, speeches, books and pamphlets to change public opinion in order to have the laws repealed. A brief examination of many of the major anti-vaccination activists and their essentially similar methods and arguments illustrates that the leaders of the movement held much in common.

Charles Higgins devoted much of his time agitating for the repeal of the compulsory vaccination law in New York. His publications included, The Case Against Compulsory Vaccination: An Appeal to Common Sense to the Governor, Legislature and People of the State of New York, by a Layman, in which he included a "New Emancipation Proclamation" that concludes with a stirring invocation.

We must see that our children's education is not predicated on the point of the poisoned quill. We must see to it that the subcutaneous injection of an absolute poison does not take the place of sanitation and hygiene . . . We must not surrender the right of personal privilege in the selection of our food, our religion, our politics or our medicine.5

These statements reveal a mistrust of vaccination, and a compelling demand for freedom of choice in matters of medicine. Higgins went so far as to threaten to lead a strike by parents of New York school children demanding the right to choose whether to have their children vaccinated.6 While Higgins never managed to have the vaccination law repealed in New York despite all his hard work, another anti-vaccinationist, James Loyster, who had lost a son as a result of vaccination complications, managed to have the law repealed after he published a lurid collection of testimonies from grieving parents in New York, which he presented to the state government.7

Another outspoken agitator, J.M Peebles, M.D., Ph.D, published ten editions of Vaccination, A Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty: With Statistics Showing Its Dangers and Criminality. In this book published between 1900 and 1913, Peebles heaps scorn on what he calls not only "the chief menace and gravest danger to the health of the rising generation, but likewise the crowning outrage upon the personal liberty of the American citizen."8 Peebles, like Higgins, argued for sanitation, diet, and mental calmness as the only certain cures for smallpox, thus offering a solution to smallpox rather than simply opposing vaccination.9

Fitness enthusiast Bernard McFadden remained a life-long advocate of clean living and diet as preventatives to disease. McFadden's Physical Culture Publishing Company published a condemnation of the procedure, Vaccination a Crime, that claimed that physicians sought compulsory vaccination for profit.10

Lora Little stands as one of the most dedicated anti-vaccinationists. She denounced vaccination as "a violation of the blood and when performed upon a man against his will [it]is a personal assault of exceptionally outrageous character."11 Little, like Loyster and another noted anti-vaccinationist, Harry Anderson, lost a child as a result of vaccine-related infection.12 She personally led a mass anti-vaccination protest by parents of schoolchildren in Portland Oregon. In 1914 that city's health officials announced that all school-children had to be vaccinated during a ten day period. Led by Lora, up to two-thirds of the city's school children defied the order and absented themselves from school while the ten days of vaccination were supposed to take place.13 As a result, the city health officials gave up on the issue. During the First World War, Little even faced trial for treason in North Dakota under the Espionage Act,14 for encouraging protests among soldiers against compulsory vaccination in the armed forces. As Johnston points out ,however, "Lora Little had the last laugh when the North Dakota Supreme Court overturned compulsory vaccination after a case resulting from her agitation."15

The anti-vaccination movement faded away during the 1920s following the deaths of many of its prominent members, since the movement itself relied on this cadre of dedicated leaders.16 While the movement existed, however, the zealous efforts of its leaders resulted in several successes against compulsory vaccination. As Johnston writes, "By the 1930s four states (Arizona, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Utah) had laws prohibiting compulsory vaccination, and only nine states and the District of Columbia had compulsory vaccination legislation."17 Though not successful everywhere, the movement formed a rallying point for the substantial minority of Americans who feared state intervention into personal health and had "clearly grown into a mass movement."18

John Pitcairn became a significant anti-vaccinationist leader in the national anti-vaccination movement as a result of a crisis experienced in Bryn Athyn over compulsory vaccination.

New Church Anti-vaccinationism before the Crisis top

It is all too easy to look either at national events apart from local history, or local history divorced from national events. The national anti-vaccination movement may have been led by prominent leaders who wrote, traveled and lectured extensively, but its support came from the small anti-vaccination minorities in cities and towns across the nation. One such anti-vaccination minority existed in Bryn Athyn and other small societies of the New Church.19 To understand the anti-vaccination movement and how it gained its leaders, principally John Pitcairn, we ought to examine the issue on the local level in places such as Bryn Athyn.

While it is impossible to say how many members of the General Church (centered in Bryn Athyn) were opposed to the idea of vaccination before the crisis, which took place in the early weeks of 1906, but a variety of sources in New Church Life attack the practice, while no New Church literature from the time defends vaccination. These sources alone prove that Bryn Athyn and the New Church possessed a vocal minority of people opposed to vaccination. Like other previously mentioned anti-vaccinationists they saw it as a dangerous medical procedure and as an insidious attack on individual freedom. What made New Church communities unique in their opposition was that some condemed the practice from the perspective of their New-Church beliefs.

The earliest recorded comments on vaccination in the New Church are those of Reverend J. Potts, whose paper was published by the National Anti-Vaccination League in England in 1882. He wrote: "It is now a well-known fact—an undeniable fact that the most frightful and revolting maladies of all human maladies is communicable, and is communicated by vaccination to little children."20 Not only was vaccination dangerous, but he asked incredulously, "How is it that the free people of this country can be brought to submit themselves to a compulsory medical operation, and how is it that the parents of this free land can be induced to hand over their new-born children to the vaccinator?"21 Potts next argued from the perspective of the New Church. "The blood of little children corresponds to innocent life. To take matter and put it into the blood of a little child corresponds to introducing the foul corruptions of hell into innocent life."22

Potts was certainly not alone among members of the New Church, in light of the following evidence of anti-vaccinationism found in New Church Life. Harvey Farrington, MD, opened his article in New Church Life by mentioning the danger to health and freedom associated with vaccination, and then shifted to a spiritual exploration of vaccination. "To the New Churchman, however, statistics alone, and the experience which they are supposed to represent, are not sufficient. He must search out the principle which governs within."23 According to Farrington, vaccination turns Divine order on its head since it addresses the most external part of the problem, namely the skin, and then works inwards corrupting everything. Healing from Divine order, on the other hand, would be to administer a medicine that would be properly digested and radiate healing outwards reaching the skin last.24

New Church people also expressed themselves through letters to the editor of New Church Life. A. Roy of Toronto wrote to suggest a book by a Dr. Scott Tebb of England, condemning vaccination which "is a most interesting and instructive book, and turns the statements of the advocates of vaccination against the practice which they seek to uphold."25 The heroine of an anonymously written novel published in New Church Life calls vaccination "from hell."26

In considering John Pitcairn's views on vaccination during this same period, we have very little firm textual evidence. We can assume that as a central figure in the Church, he read at least some of the substantial number of spiritual and natural attacks on vaccination written by other members of the New Church. If so, this may have been the source of his initial opposition toward vaccination, which in time grew to be a great issue for him. His letters, unfortunately, reveal no explicit statement of an opposition to vaccination from a spiritual level, though scraps of evidence give us clues that he probably did have spiritual reasons. William Frederic Pendleton, with whom John Pitcairn disagreed during the vaccination crisis, wrote at its height that "it became clear to me that we were making it a matter of spiritual conscience, and a fundamental of the Church."27 This is a tantalizing quote because Pendleton tactfully refuses to mention who exactly was making it a "matter of spiritual conscience." Since, however, Pitcairn was the leader of the anti-vaccination faction in Bryn Athyn, it seems likely that he was meant. Besides this, James Colgrove surmises that,

Pitcairn's opposition to vaccination was rooted partly in Swedenborgian teachings and in his devotion to homeopathy, an alternative medical practice that many Church members embraced. He was also influenced by the fact that, years earlier his son Raymond had suffered an adverse reaction to being vaccinated as a child.28

This quote provides an interesting guess29 that John Pitcairn opposed vaccination for spiritual reasons, as well as a convincing theory that his own negative experience contributed to his opposition to the practice. Regardless of whether Pitcairn believed that vaccination was spiritually wrong, it is certain that Pitcairn was strongly opposed to vaccination because he wrote to Pendleton. "That we should differ in a matter upon which I had long had deep convictions was a grief to me."30

It is uncertain how many members of the New Church agreed with these anti-vaccination sentiments. It remains clear that at least John Pitcairn and a vocal minority within the Church opposed compulsory vaccination before the crisis of 1906. Bryn Athyn and the New Church thus fit well within the national debate over vaccination, where a small but vocal minority of Americans in communities all across the nation stood in opposition to compulsory vaccination for much the same reasons. In these communities, including Bryn Athyn, some prominent anti-vaccinationists such as Lora Little and Charles Higgins rose to take a leadership role in the activism against compulsory vaccination. John Pitcairn would fulfill this role for Bryn Athyn, beginning as just another member of the community who opposed compulsory vaccination, and later rising to become a prominent national leader in the movement.

Struggle in Bryn Athyn: Vaccination Strikes Home top

For it's "Vaccination, Abomination,

Anti-Vaccinationists only can be saved!"

Or, "Vaccination, we uphold the nation,

The laws of Uncle Sam must be obeyed."

This once peaceful little hamlet,

Is now torn by bitter strife

All harmony is turned to discord,

And dissentions mar our life.31

These words from a song written in Bryn Athyn during 1906, refer to a distressing and intense debate over compulsory vaccination that split the members of the community into two camps. In early 1906 smallpox came to Bryn Athyn sparking a crisis which endangered the Academy of the New Church, and spurred John Pitcairn to become both a local and national leader in the anti-vaccination movement. Celia Bellinger, a teacher at the Academy, carried the disease to Bryn Athyn from Canada in February 1906. Until the time of the actual outbreak, the Academy had failed to act on a notice from the Pennsylvania Department of Health in 1905 that warned schools to obey the law requiring the vaccination of all school children.32 The school closed on February 16, while community leaders sought to bring the situation under control. Meanwhile, a heated debate began between members of the Church who wished to defy the law, and the majority who felt they ought to obey it. In a letter to Celia Bellinger's father on February 16, Bishop Pendleton clearly expresses what was probably a common sentiment among those who chose to submit to the law.

Vaccination is to be avoided as far as possible, but that there is a limit, and the limit is passed when we come actually face to face with the civil authorities . . . then there is nothing left but to yield. . . . I, therefore, and others acting with me here, have decided to allow vaccination, and even favor it under the circumstances, as the least of two evils. In fact there seems hardly any other choice before us, for under the stringent laws and quarantine regulations a unanimous opposition on our part to vaccination, would render our situation untenable.33

The anti-vaccination minority in Bryn Athyn disagreed with Pendleton's action and preferred to defy the state law.34 These were people who, from political, medical, and spiritual convictions, felt that vaccination was a crucial enough issue that it was worth ignoring state law to challenge it. One New Churchman, R. Carswell, wrote to John Pitcairn. "It is a great relief to find that there are three families who will not tolerate vaccination, and that your family is one of the three . . . If the officers of the civil authorities take improper action you . . . will . . . see that they are called to account."35 Carswell explained that he was willing to join Pitcairn and the others in the "resolve to protect their families." Whatever other reasons Carswell and Pitcairn had for disliking vaccination, Carswell's letter indicated that the primary issue which concerned them during the actual crisis, was the danger to health posed by vaccination.

To further illustrate the lengths to which anti-vaccinationists in Bryn Athyn would go, we can examine the case of Enoch Price. Enoch Price, who had long been opposed to vaccination, refused to be vaccinated. After being suspended from teaching and placed in quarantine, he wrote to Pitcairn that he was still strong in his convictions, but he echoed a similar tone of hopelessness to that of Pendleton. He feared that he would not be able to resume teaching after his quarantine, but more importantly, that his children would have to stay home from school unless he consented to vaccination.

Will my children be allowed to go back to the school after the quarantine is off?

. . . If they cannot go I suppose that I must eventually yield to force, but I find it difficult to give up the firm convictions of nearly twenty years.36

Price, like many anti-vaccinationists, was caught in a dilemma; on the one hand he feared vaccination, believing it would harm his family, on the other hand his opposition to it certainly would harm his occupation and the education of his children.

While Price was willing to go to the brink of sacrificing his job for anti-vaccinationism, the Reverend George Starkey held the honor of being the most extreme New Church opponent of vaccination. He confessed to John Pitcairn that he once carried a Colt automatic pistol with him in case the authorities attempted to vaccinate him.37

Though clearly principled, the sometimes extreme anti-vaccinationism in the New Church supports Pendleton's argument that opposing the state endangered the Academy. This becomes especially apparent in light of a letter sent from the Chief Medical Inspector of Pennsylvania that spelled out in no uncertain terms the futility of Bryn Athyn defying the law regarding compulsory vaccination.

General vaccination and re-vaccination is imperative. As this is compulsory in the case of school children . . . the operation should be performed at once, especially in the presence of the existing emergency. . . . School, Church or public meetings of any sort shall not be convened until further notice.38

Something had to be done to avoid a disaster for the New Church. The Academy risked collapsing as a house divided against itself, or else failing in a hopeless fight with state authorities. Pendleton and Pitcairn had several heated arguments over the subject, culminating in an exchange of letters in which both of them apologized for getting out of hand.39 Pitcairn must have realized that the opposition of members of the New Church, though justified, was damaging the Church that they all loved so much. On March 22, after another fierce debate, Pitcairn conceded to accept the Bishop's views on the matter and to stop actively encouraging opposition to vaccination in the Church.40 Richard Gladish is correct in maintaining that the "threat of a head-on collision between the little Church-school and the power of the state was avoided, and at the same time the potential of an equally serious confrontation between lay and clerical leadership in the Church and community."41

The vaccination crisis struck John Pitcairn to the core. Before Celia Bellinger contracted smallpox, members of the Church remained free to have their families vaccinated or not as they saw fit. John Pitcairn and others like him who opposed vaccination remained happy with the status quo. With the outbreak, Pitcairn was shocked to find that Bryn Athyn was not safe from the long arm of state legislation. The founders of Bryn Athyn had envisioned a place where they could live according to their beliefs; this vision must have appeared to Pitcairn to no longer be true. Fearing that resistance to the law on the local level only endangered the Academy, Pitcairn instead chose a new battlefield for the fight against compulsory vaccination. He must have realized that by using his financial42 resources and influence he could help Bryn Athyn and the Church only by changing the compulsory vaccination laws of the state. He also knew that he could perform a great service to others in his state and nation by educating people about the dangers of vaccination. Before he felt that his freedom and health and that of members of his church were threatened, John Pitcairn simply held strong convictions about the subject; now he would actively fight compulsory vaccination.

John Pitcairn and the National Anti-vaccination Movement top

Gladish aptly summarized John Pitcairn's reaction to the vaccination issue in Bryn Athyn when he wrote: "He proved too obedient a layman to continue his campaign within the Church, but he would not soften his opposition to vaccination."43 In fact, John Pitcairn increased his opposition to it and, more importantly, channeled his financial resources towards ending compulsory vaccination in his state and the nation. With the help of like-minded individuals such as Charles Higgins and Porter F. Cope, he formed his own anti-vaccination organization called the Anti-Vaccination League of America. John Pitcairn shared the ideology of the other American anti-vaccinationists, and was a significant force within the movement. He fought against compulsory vaccination for the two reasons the others did: vaccination endangered those who used it, and forcing vaccination upon anyone was an attack on personal liberty.

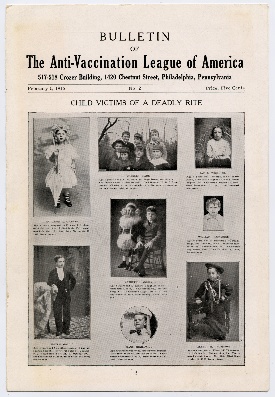

Front page of the Bulletin of the Anti-Vaccination League of America from 1916, with pictures of children who had died from complications following vaccination. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives. Click on image for a larger version.

Keeping in mind that the vaccination crisis in Bryn Athyn had faded by late March 1906, the extent of Pitcairn's anti-vaccinationism zeal becomes clear. By May 16 he had already assisted in organizing a massive anti-vaccination meeting at Witherspoon Hall in Philadelphia, and more importantly, formed the Pennsylvania Anti-Vaccination League by mid-July. The goals of the league, of which Pitcairn served as president for his lifetime, were "to secure the entire abolition of compulsory vaccination, and to conduct a campaign of education against vaccination itself."44 John Pitcairn's chief allies in the league were the secretary, Porter F. Cope, and treasurer, Charles Higgins, who was independently active in the anti-vaccination movement in New York at the same time.45 They both wrote many papers and gave many speeches as part of the Pennsylvania Anti-Vaccination League46 and along with Pitcairn formed its heart.

During his tenure as president John Pitcairn gave speeches, wrote papers, published, served on a state vaccination commission, and lobbied the state legislature. Until the end of his life he remained active in the league and consistent in his arguments against compulsory vaccination. In a speech before the Committee on Public Health and Sanitation he argued eloquently for human freedom,

One of the foundation principles of our government is absolute freedom from interference in matters of religious faith. Shall we witness unmoved the establishment by that government of a practice that deprives us of freedom in matters of medical faith? We have repudiated religious tyranny; we have rejected political tyranny; shall we now submit to medical tyranny?47

In contrast to the totally partisan literature produced by other anti-vaccinationists, the league published a small volume titled Both Sides of the Vaccination Question, which included a paper by John Pitcairn as well as a pro vaccination paper, presumably to show that the league was not afraid of comparing its arguments with those of their opponents in the medical profession. In this book Pitcairn bluntly defined the procedure illustrating its danger. "Vaccination is the putting of an impure thing into the blood—a virus or poison—often resulting in serious evil effects."48 He followed this with statistics from Japan and the Philippines related to vaccination's ineffectiveness. The arguments in Both Sides of the Vaccination Question echo those of other pamphlets published by the league and by the other leading anti-vaccinationists.

Both Sides of the Vaccination Question published by the Anti-Vaccination League of America contained an anti-vaccination paper by John Pitcairn as well as a pro vaccination paper by Jay Frank Schamberg. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives. Click on image to view the title page.

The governor of Pennsylvania, John Tener, appointed John Pitcairn to serve on a vaccination commission charged with reviewing the effectiveness of the practice. A February 28, 1912 New York Times article related how Pitcairn had spent "a great deal of money" on the anti-vaccination movement and called him and Porter Cope "the leaders among the anti-vaccinationists in this country."49 As a significant representative of the opposition, Pitcairn wrote a dissenting report at the conclusion of the commission's review. He first claimed that since vaccination was the only medical procedure required by law, a great burden of proof lay with its proponents to prove that it was effective, safe, and moral in order to make it compulsory.50 After fully sixty pages of statistics related to its ineffectiveness and danger Pitcairn concluded that "from the evidence it will be clearly seen that there is absolutely no proof in favor of vaccination, but that there is positive and undoubted proof of deaths from vaccination."51

Besides serving on the state commission, Pitcairn also lobbied the governor and legislature of Pennsylvania to repeal compulsory vaccination laws in 1907 and 1912. In the draft of a 1907 letter to Governor Stuart of Pennsylvania, Pitcairn urged him to sign into law an anti-vaccination bill that had passed the house and senate:

The State of Pennsylvania has now exercised its discretion in the modification of the existing Law, by the passage of the Watson Bill, this having passed by practically the unanimous vote of the House and by a majority vote in the Senate. I beg to call your attention to the fact that, as evidenced by thousands of petitioners, a large majority of the citizens of the Commonwealth are conscientiously opposed to Compulsory Vaccination.52

Despite Pitcairn's pleas, Governor Stuart vetoed the bill which had come so far. It is nevertheless certain that John Pitcairn's movement had gained substantial support for it to get as far as it did in the state government, and that other leaders in the anti-vaccination movement respected him for his efforts in 1907.53 Pitcairn, like Lora Little, and Charles Higgins, had not only written about vaccination, but had actually taken their fight to the legislature in an effort to end compulsory vaccination.

Pitcairn's ongoing interest in anti-vaccinationism and his presidency of the Anti-Vaccination League of America continued until his death in 1916. During that time he spent considerable sums of his money, talent, and time trying to end on the national level what he couldn't accomplish in Bryn Athyn. Ultimately he was unsuccessful in changing the law in Pennsylvania, and therefore never managed to gain freedom for the individuals of his community to exempt themselves from vaccination. To his allies in the anti-vaccination movement, he was far from a failure. Charles Higgins included a posthumous tribute to John Pitcairn in a book he published in 1916,54 and Harry Anderson included a simple but eloquent dedication to John Pitcairn in a book published in 1929 calling him, "one of the most outstanding opponents of compulsory vaccination in the United States."55 Though not the sole instigator or leader of the anti-vaccination movement, he played a key, active supporting role in its leadership.

Conclusion top

In the early twentieth century John Pitcairn joined a vocal minority of Americans opposed to the implementation of compulsory vaccination laws, and waged a war for public opinion. Those who made up the movement argued vehemently that vaccination was a dangerous medical practice, and more importantly that government had no right to impose medical procedures on a free people. John Pitcairn had never liked vaccination, but only began to fight it actively when a case of smallpox threw Bryn Athyn into turmoil. Pitcairn and others in Bryn Athyn debated whether to defy the compulsory vaccination law or submit to a practice they held strong convictions about. Pitcairn eventually conceded to Bishop Pendleton's plea that he avoid making Bryn Athyn a battlefield for his anti-vaccination efforts because they were endangering the Church. He realized that he could help end vaccination, both in Bryn Athyn as well as other communities, by joining other like-minded anti-vaccinationists on the national level. Like the other leaders in this minority movement, Pitcairn argued that compulsory vaccination posed both health risks and a threat to individual freedom. Pitcairn chose to avoid risking harm to his church, and instead played a key supporting role in the battle for public opinion in the attempt to repeal compulsory vaccination legislation.

Footnotes top

1 James Colgrove, "Science in a Democracy: The Contested Status of Vaccination in the Progressive Era and 1920s," Isis 96 (June 2005): 2.

2 Robert D. Johnston, The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 190. See also Colgrove 2.

3 Colgrove, 3.

4 Colgrove, 3.

5 Charles Higgins, The Case Against Compulsory Vaccination: An Appeal to Common Sense to the Governor, Legislature and People of the State of New York, By a Layman (New York: Charles M. Higgins, 1907), ix.

6 "Threaten a Strike over Vaccination," The New York Times, December 16, 1910.

7 Colgrove, 13.

8 J. M. Peebles, Vaccination a Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty: With Statistics Showing Its Dangers and Criminality (Los Angeles: Peebles Publishing Company, 1913), 5.

9 Colgrove, 8.

10 Ibid., 8.

11 Lora Little, The Oregonian, 1911, quoted in Johnston, 192.

12 Colgrove writes: "One very significant personal characteristic shared by prominent activists was family tragedy: Henning Jacobson, John Pitcairn, James Loyster, and Lora Little all had children who either died or suffered injury following vaccination." Colgrove, 9.

13 Johnston, 193.

14 The Espionage Act was a controversial war measure intended to silence any opposition to the war effort, by placing it on the level of sedition.

15 Johnston, 210.

16 Colgrove, 16.

17 Johnston, 183.

18 Johnston, 178.

19 The focus of this section and the next is the anti-vaccination movement in Bryn Athyn, but as many of my sources are letters, and letters were not typically written between people in Bryn Athyn, many of our best sources do not come from Bryn Athyn even if they are applicable to attitudes there.

20 J. F. Potts, Vaccination: A Paper Read Before the Meeting of the Swedenborg Reading Society (London: National Anti-Vaccination League, 1882), 2.

21 Ibid., 3.

22 Ibid., 6.

23 Harvey Farrington, "Vaccine, Antitoxin, and the Rest," New Church Life (1899): 76.

24 Farrington, 77.

25 A.K. Roy, "Vaccination Arraigned," New Church life (1899): 41.

26 New Church Life, "The True Story of One Girl's Life: Chapter VIII," (1886): 9.

27 William Frederic Pendleton to Bellinger. February 16, 1906. Swedenborg Library Archives, Academy of the New Church.

28 Colgrove, 5.

29 I call it a guess because Colgrove provides no specific source for his statement of Pitcairn's spiritual reasons, and because I could find none.

30 John Pitcairn to William Frederic Pendleton. March 27, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

31 "Vaccination Abomination, 1906 [?]," John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

32 Richard R. Gladish, John Pitcairn: Uncommon Entrepreneur (Bryn Athyn, PA: Academy of the New Church, 1989), 330.

33 William Frederic Pendleton to Bellinger. Feb 16, 1906. Swedenborg Library Archives, Academy of the New Church.

34 Gladish, 30.

35 R. Carswell to John Pitcairn. February 19, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

36 Enoch Price to John Pitcairn. February 18, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

37 Rev. Starkey to John Pitcairn. February 21, 1906. May 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

38 Fred Johnston to C. Doering. February 19, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

39 John Pitcairn to William Frederic Pendleton. March 27, 1906. And William Frederic Pendleton to John Pitcairn. March 26, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

40 Gladish, 331.

41 Gladish, 332.

42 This author has not made an exact tally of the exact amount of money expended by Pitcairn in his anti-vaccination efforts. The amount was substantial, however, based on numerous letters containing records of expenses found in the John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives. It is also worthy to note that this author did not make a detailed study of how much other anti-vaccinationists contributed to the anti-vaccination cause.

43 Gladish, 332.

44 Porter Cope to Cyriel Odhner. December 4, 1906. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA. Porter F. Cope provides a good outline of Pitcairn's involvement in the anti-vaccination movement in his lengthy letter to Cyriel Odhner, which can be found in the John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives.

45 Charles Higgins was briefly mentioned in the first section. Colgrove also gives a brief and excellent survey of his life.

46 The Pennsylvania anti-vaccination league later changed its name in 1908 to the Anti-Vaccination League of America but this did nothing to change its goals or organization.

47 John Pitcairn, Vaccination: An Address Delivered before the Committee on Public Health and Sanitation of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: The Anti-Vaccination League of Pennsylvania, 1907), 1.

48 John Pitcairn and Jay Frank Shamberg, Both Sides of the Vaccination Question (Philadelphia: The Anti-Vaccination League of America, 1911), 9.

49 "Orders Smallpox Inquiry: Pennsylvania Commission to Determine the Value of Vaccination," The New York Times, January 28, 1912.

50 John Pitcairn, "Dissenting Report of John Pitcairn, Commissioner." In The Pennsylvania State Vaccination Commission: Report and Dissenting Reports, unknown editor, 156–228 (Philadelphia: Allen Lane & Scott, 1913), 156.

51 John Pitcairn, "Dissenting Report," 227.

52 John Pitcairn to Edwin Stuart. May 17, 1907. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

53 John Pitcairn received several consolatory letters including one from U.S senator George Oliver who expressed his disappointment that the "very reasonable bill" did not pass and assured him, that he "did everything that I could to secure its adoption." See George Oliver to John Pitcairn, February 11, 1914. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

54 Colgrove, 9.

55 Harry B. Anderson, The Facts Against Compulsory Vaccination (New York: Citizens Medical Reference Bureau, 1929), x.

Bibliography top

Anderson, Harry B. The Facts Against Compulsory Vaccination. New York: Citizens Medical Reference Bureau, 1929.

Bulletin of the Anti-Vaccination League of America. February 1, 1916, no.2. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Colgrove, James. "Science in a Democracy: The Contested Status of Vaccination in the Progressive Era and 1920s." Isis 96 (June 2005): 1–26.

Davidovitch, Nadav. "Negotiating Dissent: Homeopathy and the Anti-Vaccinationism at the Turn of the Twentieth Century." In The Politics of Healing: Histories of Alternative Medicine in Twentieth-Century North America, edited by Robert D. Johnston, 11–28. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Farrington, Harvey. "Vaccine, Antitoxin, and the Rest." New Church Life (1899): 76–77.

Gladish, Richard R. John Pitcairn: Uncommon Entrepreneur. Bryn Athyn, PA: Academy of the New Church, 1989.

Higgins, Charles M. The Case Against Compulsory Vaccination: An Appeal to Common Sense to the Governor, Legislature, and People of the State of New York, By a Layman. New York: Charles M. Higgins, 1907.

Higgins, Charles M. "To the People of Brooklyn: Is Compulsory Vaccination Justifiable?" 1909. John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Johnston, Robert D. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Little, Lora. "Mass Meeting in Philadelphia." The Liberator (June 1906): 78–80.

Millard, C. Killick. The Vaccination Question In the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration. London: H. K. Lewis, 1914.

New York Times, December 16, 1910. "Threaten a Strike over Vaccination."

New York Times, January 28, 1912. "Orders Smallpox Inquiry: Pennsylvania Commission to Determine the Value of Vaccination."

New York Times, May 5, 1914. "Higgins Opposes Child Vaccination."

"Notes of a Speech Delivered at Colchester, June 19, 1900." New Church Life (1900): 503.

Peebles, J. M. Vaccination: A Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty: With Statistics Showing Its Dangers and Criminality. Los Angeles: Peebles Publishing Company, 1913.

Pitcairn, John. Vaccination: An Address Delivered before the Committee on Public Health and Sanitation of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: The Anti-Vaccination League of Pennsylvania, 1907.

Pitcairn, John. "Dissenting Report of John Pitcairn, Commissioner." In The Pennsylvania State Vaccination Commission: Report and Dissenting Reports, unknown editor, 156–228. Philadelphia: Allen Lane & Scott, 1913.

Pitcairn, John, and Jay Frank Shamberg. Both Sides of the Vaccination Question.Philadelphia: The Anti-Vaccination League of America, 1911.

Potts, J. F. Vaccination: A Paper Read Before the Meeting of the Swedenborg Reading Society. London: National Anti-Vaccination League, 1882.

Roy, A. K. "Vaccination Arraigned." New Church Life (1899): 41.

"The True Story of Once Girl's Life. Chapter VIII." New Church Life (1886): 9.

"Vaccination Abomination, 1906[?]." John and Gertrude Pitcairn Archives, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Revised 4/13/2006