Messengers of New Light:

William Henry

Benade and

Lillian Grace Beekman

Mary Ann Meyers

Presentation, Glencairn Museum

Bryn Athyn, PA, September 24, 2004

|  |

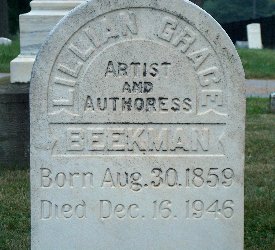

Lillian Grace Beekman (1859–1946). She was buried in Romeo, Michigan, alongside members of her family. A photograph of her headstone was taken in August of 2005. Photo (left): Academy of the New Church Archives, Swedenborg Library. Photo (right): Tom Raymond. Click on images for a larger version.

My title is taken from a letter written by Bishop William Frederic Pendleton. He presided over the General Church at the founding of Bryn Athyn. William Henry Benade was his predecessor, the General Church Moses who was destined to view the Promised Land from the Moab plains. Lillian Grace Beekman was Bishop Pendleton's colleague and friend, the first woman to teach theology at the Academy. I apply the phrase he used to describe her knowing that some may find it ironic. But is it? My subject is hermeneutics. I have accepted your gracious invitation with the hope that by drawing on my research into the construction of this unique community, I can say something you may not know, or remind you of things you may have forgotten, about the ways in which two singular people in your history interpreted the Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Both parted company with the community under dark clouds, of madness on the one hand and of apostasy on the other; nevertheless, they sought mightily for a time to illuminate the Word for believers. Furthermore, as I have reacquainted myself with Beekman's story, I realize that my more recent acquaintance with the path-breaking work of a contemporary feminist theologian in the old church has given me a new lens with which to view her meteoric sweep though Bryn Athyn that began 105 years ago.

The Academy movement coincided with the initial groundswell for women's rights in America after the Civil War. The rise of cities in which growing numbers of women found some measure of economic independence, the establishment of separate women's colleges, the suffrage movement, female assumption of leadership in the temperance crusade, and nationally coordinated efforts to secure reform of divorce laws, all of these straws in the wind were bound at least to brush the emerging Swedenborgian communion. Militant feminism could not be expected in a religious group that ascribed canonical status to a work proclaiming: "Women who think like men concerning religious things, and speak much concerning them, and still more if they preach in assemblies, destroy the feminine nature. . . ."1,2 To be sure, Swedenborg appears to posit the existence of distinct and unchanging masculine and feminine essences. But he also insists that no qualities of mind are the exclusive possession of either sex. Did he intend the dichotomy of understanding versus will to be contemplated in terms of gender? How the Writings are interpreted is, of course, critical because the General Church of the New Jerusalem made its stand in opposition to other readers of the Swedish seer on the basis of their authority.

But let us step back from that key issue for a moment to review briefly some history, which is undoubtedly familiar to many of you. James Glen, a Scottish plantation owner from what is now the South American republic of Guyana, introduced the heavenly doctrines to America in 1784 when he delivered a lecture on the Writings in Philadelphia. Within a few years, thanks to an influential member of Glen's audience, Francis Bailey, who was the editor and publisher of the Freeman's Journal, what the revolutionary poet Philip Freneau termed "Emanuel Swedenborg's universal theology" was creating what today we would call a buzz. By 1808, a group of about twenty quite distinguished professional and businessmen were meeting regularly to discuss the Writings. Eight years later, Philadelphia believers had a church building, a liturgy, and a priest—a former lay-reader who had been ordained by the American New Church patriarch, Baltimore's John Hargrove. But when ill health forced the Rev. Maskell Carll to take a long recuperative journey to England, lay readers again conducted services, as they had before his ordination. Among them was a young man named Richard de Charms. The son of a Huguenot physician, he subsequently studied first with Thomas Worcester, a prominent New Church clergyman in Boston, then with Hargrove, and was ordained by the latter in 1828. De Charm's leadership potential was quickly recognized, and he played a prominent part in national New Church affairs.

His interest for us this evening is his position on the Writings and his role in the conversion of a Moravian minister. In opposition to his former mentor, Worcester, and more forthrightly than any American before him, de Charms wrote: "I am rationally convinced that Swedenborg was fitted and commissioned to teach the Doctrines of the New Church from the Lord immediately, therefore his doctrines are the Lord's doctrines, and are to be received with the Lord's authority."3 Inextricably linked to this question about the authority of the Writings were others about the state of the Christian world and the importance of New Church education. De Charms argued persistently for day schools, and as the result of his efforts, they were established in a few societies. But more successful in the long run was his missionary outreach, especially a trip in the autumn of 1844, which took him to Lancaster where he met the then twenty-eight-year-old William Henry Benade. Benade's father was a Moravian bishop, and he had ordained his son, a graduate of the Moravian Theological Seminary, in 1841. Two years later, the young minister began to study the Writings, and in 1844 de Charms became his spiritual director. He baptized Benade the next year, licensed him to preach, and ordained him as a New Church priest in 1847.

William Henry Benade (1816–1905). Photo: Academy of the New Church Archives, Swedenborg Library. Click on image for a larger version.

Benade served as pastor of the Philadelphia First Society for nine years. But the priest's High Church views and the "Quaker" preferences of his congregation eventually necessitated a separation. With a number of sympathizers, he formed a new society, whose members not only subscribed to his ideas about the use of representatives in worship, but also accepted his view of the preeminence of education among church functions. In 1857, Benade and some of his key supporters opened a school on Cherry Street, and even more importantly, established a sub rosa organization of New Church scholars. Known as the Academy, it was formed for the purpose of explicating Swedenborg's works, propagating the members' belief in the Writings's divine origins, and training young men for the priesthood. In a striking analogy, Benade compared the "natural womb of the Virgin and the mental or internal sensual scientific and rational womb or matrix found in the mind of Emanuel Swedenborg."4 The Swedish seer, then, played the same role in the eighteenth century as that played in the first-century by Mary of Nazareth. Swedenborg "was called into a new and unheard office and miraculously fitted for it," another Academy member said.5 Benade spoke out forcefully in defense of an episcopal polity. He called not only for a triadic order of ministers with distinct functions but also an organization governed by a presiding bishop acting in consultation with a clerical council. In purely ecclesial affairs, the laity was to have no part for "it is the, Priesthood," Benade said, "which makes the Church."6

The uses of the Academy could not be carried out by the clergy alone, however, for the support of research and the publication of books, to say nothing of the establishment of schools, were costly ventures. Financial backing was essential, and for it, Benade turned to the laymen of means. No one was more generous than John Pitcairn. An immigrant from Scotland, Pitcairn was received into the New Church as a boy when his parents accepted its teachings shortly after their arrival in western Pennsylvania. He met Benade, twenty-five years his senior, at the age of nineteen when he came to Philadelphia as secretary to the superintendent of the Philadelphia division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1874, Pitcairn was having lunch with a nucleus of Academy members when they launched what they called the "New Church Club" and elected Benade president. Two years later, they renamed themselves the "Academy of the New Church." Benade, who had been elevated to the New Church office of ordaining minister, added the title of chancellor to that of bishop in 1876. A theological school and a college were established in Philadelphia—and within a few years, schools for boys and girls. In 1880, Benade presided over what had become an annual nineteenth of June celebration commemorating the birth of the New Church in the spirit world. It was held that year in an idyllic country setting near Alnwick Grove, later Bryn Athyn.

But beneath the placid surface, there were the first stirrings of concern over the increasing concentration of power in the hands of one man. When the Academy and the formal ecclesial body of which it was a part, the General Church of Pennsylvania, severed ties with the national body of Swedenborgians in 1890, the worry grew. On doctrinal grounds, the separation was inevitable. But close observers were troubled that Benade appeared to view the Academy as an interior and superior ecclesial body within the New Church. He had had a stroke during a visit to London the previous year, and his rule seemed to many to become increasingly autocratic. Old, ill, once divorced—and now recently widowed, the chancellor was irascible, suspicious, and intolerant of others' views. He demanded that the Church be governed not by a bishop who was the first among equals, but by a high priest responsible to the Lord alone. No appeal from his judgments was countenanced, but Benade did suggest that should the supreme ruler go "utterly wrong," members of the Church might "depart from him."7

And so they did, in 1896, after the aging chancellor turned on the one man whom he had himself raised to the third degree of ecclesial orders when he consecrated him a bishop. William Frederic Pendleton, a former captain in the Army of the Confederacy, a physician before he studied for the priesthood, and now the vice chancellor of the Academy, bore the burden of his brother priests' unarticulated hope for the future of the New Church. He had become head of the theological school, and during Benade's long sojourn in England in 1893–94, when the chancellor married for the third time, Pendleton and others began establishing residences in Bryn Athyn, where Benade had previously determined to remove the Academy. Upon his return, however, the chancellor roundly denounced the project. To other priests, he suggested that Pendleton was sabotaging the Academy, and on a chance meeting, he insulted him to his face. Pendleton resigned his office, and when Benade would not withdraw his charges, other clergy withdrew from the Academy as well, along with almost all of the members of the congregation worshipping in Huntingdon Valley. An emergency meeting of the lay corporation of the Academy was called, and as the directors sought to deal with the profound crisis confronting their church, Benade unexpectedly appeared—a tall, imposing figure with luxuriant white whiskers. The old bishop announced to the directors that he had substituted his will for God's, and he resigned as chancellor.

The General Church of the New Jerusalem was reorganized under Bishop Pendleton at the same time its members established a community on the banks on Pennypack Creek. Benade had forbidden women to speak at New Church assemblies, but Pendleton relaxed restrictions upon their participation by declaring that they might properly join in "whenever there is a strong affection involved" as in the ratification of a pastor or of a name for the Church.8 He also welcomed to the Academy and the new community a brilliant and beautiful woman who would be at the center of a vortex that engulfed Bryn Athyn for the next fifteen years. Her name was Lillian Grace Beekman, and for a time she seemed clothed with the sun. One of the New Church priests who sat at her feet described her as an angel "sent to our copper age."9 To others, especially John Pitcairn, she came to seem a despoiler whose ideas and very presence represented a threat to the authority of the Writings themselves. The object of Beekman's desire was spiritual truths. Her meditations, research, and writing absorbed all her energy. In light of her avoidance, after a failed first marriage, of romantic relationships, it is possible that an element in the vituperation directed against her was a wounded male ego. In any case, it is certain that when the "angel" departed some grown men wept; others drew the first easy breath they had drawn in years.

The daughter of a Congregational minister, Beekman was born in a small Minnesota town in 1859. As a child, she lived in various Midwest parsonages. She read prodigiously from the books in her father's extensive library, and from her earliest years was drawn to classic works of mysticism. Her prayer life reflected their influence. She practiced meditation in a closet. "After awhile," the grown Lillian recalled, "I stopped saying prayers in words. . . . I just lifted up my heart for Him to see and read . . . all its longings." It was a radical ceding of control. Submission, if you will, by a powerful if still emerging intellect. God, she said, "was the romance of her heart."10 You will find similar language in Theresa of Avila and John of the Cross. Beekman seems to have been expressing the deep entanglement of sexual desire and the desire for God created, as a contemporary theologian has suggested, by "the incarnational flow of the divine to the human and the enabling thereby of the human response."11

But she was distracted for a time by an altogether earthly attachment. After studying music at Illinois's Rockford Female Seminary (the alma mater also of Jane Addams), then art, and in connection with drawing classes, anatomy, Beekman was married in the late 1880s to Edward Stieglitz, a surgeon and a younger brother of the famous photographer and New York gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz. Her husband, a non-practicing Jew from a wealthy and cultured German-American family, disapproved of her interest in religion. He also objected to having children because he feared that a strain of insanity that affected some of his relatives might be passed on to his own offspring. Beekman later told a friend that when she became pregnant, Stieglitz insisted she have an abortion and found someone to perform it.12 Not only was the procedure likely to have been extremely dangerous, but also everything we have learned about the impact of abortion on women in an era when it has become (sadly) far less rare than in Beekman's time, tells us that the experience probably had profound and lingering effects. But the unhappy marriage did not last long. Beekman took a job as a ghostwriter for a popular Chicago preacher, and she began to read Swedenborg to whom she had been introduced through the essay on the seer that Ralph Waldo Emerson included in Representative Men.

Identified as a borrower of the Principia from a New Church bookstore, Beekman was invited to attend a meeting of the Swedenborg Philosophy Club. Her subsequent participation in its affairs moved L. P. Mercer, the priest-in-charge, to write about Beekman to Bishop Pendleton, and she first met the primate when he came to Glenview to preside at the Second General Assembly of the General Church in June 1898. She attended the conclave as a guest, and shortly afterwards was baptized into the New Church. In December, she presented her first paper to the Philosophy Club. Members soon engaged her to undertake on their behalf a major scholarly project—linking the doctrine laid out in the Animal Kingdom with contemporary physiological understanding of the body. Bishop Pendleton, the former physician, wrote to the Chicago New Church community that he believed Beekman "was able to do work that would be of great use."13 Mercer began to feel that it would be of even greater benefit if carried out in the New Church's educational center where it could stimulate other students. He described her capacity for research and analysis to Pendleton, adding that she "looked for direction to make it useful." Beekman wrote to the bishop that she should feel "the happiest freedom" in submitting her "own tentative work to the correction" of his "authority."14

An invitation to pursue a year of subsidized study in the Academy's theological school was soon in her hands. For a term in 1899 and then in 1901, as a permanent resident, she settled down to work in Bryn Athyn. Beekman was received as a member of the General Church, and before the year was out, the Academy Book Room had published her Spectrum Analysis and Swedenborg's Principia. A perpetual light seemed in burn in her window as her lonely labor of composition kept her at her desk far into the night. Still, four months after her arrival, she received a proposal of marriage from the scion of an old Quaker family, who had embraced the heavenly doctrines and moved from Philadelphia to Huntingdon Valley. She crafted a gentle refusal and went on to carefully cultivate friendships with the women of the community. Bishop Pendleton's wife became her ally and confidante. From the first days of her residence, she had conducted informal seminars in her room for theological students and ministers, as well as their wives, whom she always insisted attend her sessions with their husbands. In 1902, she began teaching anatomy and physiology in the Academy's education department, but continued her research and writing.

After several years of intensive study, Beekman's interests began to shift from Swedenborg's science to his theological treatises. She began to write on the process of creation, an effort that resulted in her second book, Outline of Swedenborg's Cosmology, published in 1907. The volume was an attempt to show the harmony between the seer's early and later works, and in this connection, she had written for her class the previous year a series of "Physiological Lectures," published in 1917 under the title The Return Kingdom of the Divine Proceeding. Typescripts of the lectures received a fairly wide circulation, and aroused both considerable interest and, not unexpectedly, criticism over the propriety of a woman teaching anything that smacked of a rational and systematic clarification of faith. Bishop Pendleton publicly defended his protégée, and in a letter to his wife noted: "Everyone who entered into the interior of their use, entered into the sphere of theology. That is what Beekman ha[s] done, and what each one ought to do in his own use."15

But the controversy continued over a series of issues—and three, in particular, sparked widespread debate. One was vaccination for smallpox. The bishop, not surprisingly given his scientific background, favored it. John Pitcairn crusaded against it. Beekman, one of the first to be inoculated with the cowpox virus herself, acceded to Pitcairn's request to read some of his campaign literature—and for a time appeared to switch sides. Detractors claimed she was motivated by economic self-interest, as the philanthropist supplemented her institutional salary. In 1912, when the medical dispute had burnt low and a theological-political one was about to flame, Beekman wrote to Pitcairn that he could consider her "with the Bishop in the affair of the old vaccination trouble."16 Years later, she accused him of betraying her into "an utterly false position." Pendleton, so she said, had understood her apparent desertion as a stance taken for the good of the General Church lest its principle financial backer "leave the Academy movement to shift for itself."17

The second dispute involving Beekman that wracked the developing community was about the bodies of angels. In 1911, a British priest published an article in New Church Life, purportedly based on Beekman's teachings, in which he disputed passages in Heaven and Hell (74–77) where Swedenborg attests to the human form of spirits he encountered on his otherworldly journeys. Two young American disciples of the Academy's only woman teacher took up the argument for bodiless angels. Priests who insisted upon a literal interpretation of the descriptions in Heaven and Hell protested that not only was the Beekman claque misreading the seer's most-studied treatise but also that it was elevating the seer's so-called preparatory works to the same plane as the Writings.

If facets of the academic argument eluded the lay community, they nevertheless followed it with interest. John Pitcairn informed Beekman that he wished to discuss the matter with her; but she rebuffed him, referring him to Bishop Pendleton instead. Pitcairn was soon backing the clergy who opposed idealism, and he demonstrated his personal displeasure with Beekman by withholding, in the summer of 1913, her customary vacation check. As his health deteriorated, and presumably his concern over precisely what form he might anticipate assuming in the spirit world increased, the philanthropist grew more hostile toward the proponents of what he called the "detestable doctrine."18 To Nathaniel Dandridge Pendleton, the bishop's younger brother who had recently been named assistant bishop, he wrote in the bluntest language:

The view held that Miss Beekman is an oracle, a "prophetess," as she has been termed; that her views must not be attacked; that she is sacred because she is a woman; has done more harm to the Church than her followers realize. We all agree that woman is sacred; but when she assumes the functions that properly belong to the masculine mind, especially those of the priesthood, her teachings are not sacred, and are a proper subject for discussion and even criticism.

Asserting that a "pervasive feminist sphere . . . exists in Bryn Athyn" that reverses "the true order given in the Heavenly Doctrine and is destructive of the conjugial," Pitcairn concluded: "I do not wish to be understood as discrediting the very valuable work of Miss Beekman on the scientific and philosophical planes. What is objected to is her position as a theological professor, and her teaching of new and strange dogmas which we believe to be contrary to the fundamental teachings of the Church."19 The assistant bishop replied that Beekman's view on angelic forms should receive neither official sanction nor condemnation. "The Writings are recognized as the doctrinal authority," he said, and "the Church as an organization should recognize the individual's right of interpretation, and indeed the right of giving it expression."20

Even as Pitcairn went on to protest against the hierarchy's failure to denounce Beekman's theory of bodiless angels, she lost interest in it. The third and final controversy in which she played a central part involved the nature of the Holy Supper. Beekman had long shared with William Pendleton a deep appreciation of the power of liturgy. But it was only in 1912, in answer to a question put to her by his brother, that she prepared a lengthy manuscript in which she discussed for the first time what she called a "sphere" proceeding from the Lord's "Palestine body." That the divine emanation entered bread and wine at the words of invocation, she declared to be the plain meaning of the Writings thitherto unperceived by the New Church.21

Now what Swedenborg wrote in The True Christian Religion is that the sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion are "two gates through which a man is introduced into eternal life."22 He portrayed the latter as "a signature and seal that those who approach it worthily are sons of God," but he also wrote: "Conjunction with the Lord is effected by the Holy Supper."23 The constitution adopted in 1787 by the London Society of Swedenborgians to which the General Church can trace its roots repeated the transitive verb and added "taken in the New Church, according to its heavenly and Divine correspondent."24 It was to administer the sacraments that the earliest readers of the Swedish seer instituted a priesthood by the laying of hands upon two old church clergymen and, by this rite, inaugurating them into the ministry of the New Church. Beekman's exegesis of the Word was that worshippers partaking of the Lord's body and blood "become," in her anatomical description, "the heart and lungs of our whole universe, the grand man, himself."25

Three controversies: the first over vaccination, which can be seen as political albeit ostensibly scientific; the second over angelic forms, which some thought a matter of metaphysics; and the third over the Real Presence, which was undeniably theological. Lillian Grace Beekman would not, it seems, keep silent in the realm of discourse that John Pitcairn, among many New Church people, considered the province of clergymen. But Bishop Pendleton's support of her was unwavering. "I have fondly cherished the thought," the prelate wrote to his protégée, "that the truth that has come to us, of the Lord's mercy, through your instrumentality, has been given to us to renew and save, to give our body reason for its separate existence, and to prevent what might have become a state of opaque crystallization. . . .You, my dear friend, came as a messenger of new light. . . . But . . . let us also be willing that others should speak freely what is in them, for in the preservation of freedom of thought and speech is the hope of all future amendment and growth."26 Pendleton would grant the same intellectual liberty to everyone.

But the dénouement was at hand. Pitcairn told Beekman that he had not been in sympathy with her views for some time and was discontinuing his personal financial contribution to her work. At the annual joint meeting of the council of the clergy and the executive committee (later called the board of directors) of the General Church in June of 1915, he brought up the subject of the state of the Church. But before he raised it, William Pendleton announced his retirement as bishop to take effect at the close of the meeting. Still, the philanthropist, ailing and distraught, read a letter he had recently sent to a friend in which he said: "The Academy is sick, very sick, and Bryn Athyn . . . has become a center for heresy. . . . The suggestion is insinuated that the Lord's Revelation to the New Church through the instrumentality of Swedenborg is not the final revelation; that we may have, and actually do have, a prophetess—a Deborah—to give to the Church an 'interior,' a celestial view, opposite to the plain and lucid teachings of the Writings on fundamental doctrines. An altar has been erected in Bryn Athyn. It is dedicated to Mystery." Pitcairn claimed that the "new views thrust upon the Church" were "theosophical," and asked: "Where are these 'new concepts' going to end?"27

Deborah, the prophetess mentioned in the Book of Judges who inspired General Barak to lead the Israelites in battle against the Canaanites? Or is there, as I hinted earlier, a resemblance between Beekman and the Spanish Christian mystic, Theresa of Avila? Or perhaps Anne Hutchinson, the woman driven from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for setting her private revelation above the public errand? Beekman was not, I must make clear, banished from Bryn Athyn. She left of her own accord. Nor was she drawn, as John Pitcairn believed, to theosophy, the exotic religious philosophy propounded by Madame Blavatsky, who settled for a while in Philadelphia and claimed to have been instructed by the Masters in Tibet. Beekman broke her ties with the New Church because, as she wrote to Bishop Pendleton, she discovered that the Trinity, the mystery of three persons in one Godhead, had been unperceived but present in her "reading, understanding, [and] labor" all along.28 Acknowledging that no interior explanation of the Writings could explain away Swedenborg's explicit denial of a "son from all eternity," Beekman withdrew from the General Church, a move she well understood would involve her dismissal from the Academy.29 She concluded, reluctantly I believe, that Swedenborg was a false witness. Donating her library of some 2,000 books to the Academy, she made a gift of her papers to Mary Pendleton, the bishop emeritus's wife. The day after she left the community, she was received into the Roman Catholic Church. Bryn Athyn's residents concluded, some earlier, some later, that Beekman was an apostate. But with a common sense of relief, they stepped back from the precipice to which deep and acerbic disagreement over her role and teachings had led them.

John Pitcairn saw her repudiation of Swedenborg as a "rescue" effected by the Lord who in His mercy "protected" the Church.30 Others were not so sure what to make of it or of Beekman herself, even though most of them felt safer with her gone. And what about you? or me, you may well ask, three decades after I first conducted the research for Jerusalem on Pennypack Creek? Let me try to answer that question by telling you about a sermon that the theologian I quoted earlier this evening gave last month, using as her text the beginning of the twelfth chapter of Revelation: "A great portent appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet; and on her head a crown of twelve stars." You have gazed for years at a beautiful stained glass representation of the female form that came to John in a vision on Patmos. It looks down on worshippers from the central light of the great west window in your cathedral-church. This symbol of the New Church, which has long challenged artists and writers in the old one, has been interpreted in many ways over the centuries—and therein lies its power. Is the woman Asherah, the Shekinah, a feminine adjunct to the Jewish deity? Israel? The Daughter of Zion? Or Mary, the mother of Jesus? The Anglican priest and theologian Sarah Coakley suggests that if the woman is Mary then she is also "representative . . . of the . . . Church," which is constituted by all believers "repeatedly making acts of consent to God—of saying Yes . . . when we could say no; of choosing life over death . . . of bringing forth, with much pain and labor, the birth of Christ among us."31

I think it is possible that Lillian Grace Beekman took up her work as a student of the Writings and a teacher in the Academy as a means of saying Yes. She gave her consent to what seemed to her, for a time, a divine calling, a vocation that appeared to her as genuine as William Henry Benade's seemed to him. Of course, we all have a profound capacity for deceiving ourselves, for misinterpreting God's will—or, as the old chancellor put it, "substituting" our will for the Lord's. But I suggest the challenge of interpretation is as important in the New Church today as it was in the Church's earliest years. Who should teach theology? Who should preach? The answers surely are to be found by looking, with an open mind, a humble heart, and an ever-sharp eye, at your doctrine of use in all its richness and layered meaning.

Footnotes top

1 Spiritual Diary, 5936.

2 The Precursor (1837), p. 61.

3 Spiritual Diary, 596.

4 William H. Benade, "Report On the Priesthood and Grades in the Priesthood," Convention Journal, 1875, p. 91.

5 James Park Stuart to William Henry Benade, December 28, 1863. Academy Archives

6 Benade, "Report On the Priesthood and Grades in the Priesthood," p. 91.

7 Quoted by Carl Odhner, The History of the General Church, vol. 14 (1894), p. 189.

8 Journal of the Third General Assembly of the General Church of the New Jerusalem, 1899, p. 47.

9 Eldred E.Jungerish to Lillian Grace Beekman, December 17, 1917. Academy Archives.

10 Lillian Grace Beekman to Mrs. Alfred Acton, September 25, 1941. Academy Archives.

11 Sarah Coakley, "The Woman at the Altar: Cosmological Disturbance or Gender Subversion," Anglican Theological Review, January 2004, p. 92, note 36.

12 See Alfred Acton, "Lillian Grace Beekman," The New Philosophy, vol. 56 (1953), p. 91, note 3.

13 W. F. Pendleton to L. P. Mercer, March 16, 1899. Academy Archives.

14 L. P. Mercer to W. F. Pendleton, May 15, 1899 and Lillian Grace Beekman to W. F. Pendleton, June 9, 1899. Academy Archives.

15 W. F. Pendleton to Mary Young Pendleton, February 7, 1906. Academy Archives.

16 Lillian Grace Beekman to John Pitcairn, May 21, 1912. Academy Archives.

17 Lillian Grace Beekman to Mrs. Alfred Acton, April 16, 1943. Academy Archives.

18 Quoted in Lillian Grace Beekman to W. F. Pendleton, April 26, 1914. Academy Archives.

19 John Pitcairn to N. D. Pendleton, August 18, 1914. Academy Archives. Italics mine.

20 N. D. Pendleton to John Pitcairn, September 12, 1914. Quoted in Journal of the Sixteenth Meeting of the Joint Council of the General Church of the New Jerusalem, November 27–28, 1915, p. 68f.

21 See Lillian Grace Beekman, "The Divine Human," unpublished manuscript, 1912, and Paper IV "On the Real Presence," unpublished manuscript, 1814. Quoted by Acton, p. 122f.

22 True Christian Religion, 777.

23 Ibid., 728 and heading to 725.

24 Robert Hindmarsh, The Rise and Progress of the New Jerusalem Church (London: Hodson and Sons, 1861), p. 57.

25 Remarks made by Beekman to Homer Synnestvedt, January 194. See Journal of the Joint Council, November 27–28, 1915, p. 153.

26 W. F. Pendleton to Lillian Grace Beekman, May 9, 1913. Academy Archives.

27 Journal of the Fifteenth Meeting of the Joint Council of the General Church of the New Jerusalem, June 26, 1915. Quotations pp. 4f, 11, and 19.

28 Lillian Grace Beekman to W. F. Pendleton, July 19, 1915. Academy Archives.

29 Lillian Grace Beekman to W. F. Pendleton, July 20, 1915. Academy Archives.

30 Journal of the Sixteenth Meeting of the Joint Council of the General Church of the New Jerusalem, November 27–28, 1915, p. 116.

31 Sarah Coakley, Sermon preached on the Feast of the Assumption, August 15, 2004, SS Mary and Nichols, Littlemore, p. 3. Quoted with permission of the author.

Revised 8/31/2005