Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church

E. Bruce Glenn

The Metal Work

TO SHEATHE THE TIMBER ROOF, Pitcairn sought a metal which would combine strength and resistance to corrosion from the elements. His search led to consideration of monel metal, which had been successfully employed for several public buildings. Monel is a natural alloy of nickel (67 percent) and copper (28 percent), with a small proportion of other metals. Mined in Nova Scotia and Ontario, it has proved over the years a highly satisfactory roofing material for the nave and chancel, and the Choir Hall as well.

It is as an art metal, however, that monel was used with results that are perhaps unique. The characteristics of this metal make it at once a challenge and a delight for artistic use in screens, grilles, and ornamental hardware. It is very tough, more difficult to work with than iron, and can be welded only by means of oxygen and acetylene. On the other hand, it will not rust, maintaining a white, nickel-like beauty without being disagreeably reflective. When hand beaten, its surface presents a pleasing texture of light and darker tones. Also, when exposed to the elements it develops a lovely patina of gray-green. Some of these effects may be noted in individual pieces about the Cathedral.

As was the case with the wood work, Raymond Pitcairn established the art metal studio and forge independently of the architects in Boston. This was in the winter of 1915–1916, and formed another step toward the complete transfer of architectural direction to Bryn Athyn. In addition to two capable metal workers, Pitcairn hired as metal design artist Parke E. Edwards, a young man who had only recently graduated from a Philadelphia art school. This choice was a matter of some discomfiture to the older designers in the architectural studio; but Edwards' promise and Pitcairn's judgment bore fruit in some of the most sensitive design work to be found in the Cathedral. When Edwards was called to Washington to do anatomical drawings as part of the war effort, Pitcairn continued to consult him; and he returned for many years of creative labor.

The first design on which he worked was the screen that separates the chapel from the south transept. This screen was first designed in a full scale wash drawing for study in place. When it came to making the screen itself, it was thought at first that it would have to be shaped from sheets of monel, in view of forging and welding problems. With the newer welding techniques, however, it could be wrought from solid strips—a decision that was to be applied throughout the church, and which was surely a happy one in the greater strength that resulted.

The chapel screen in place. It represented a triumph of experimentation with solid strips of the beautiful but difficult monel, a natural alloy of nickel and copper. Click on image for a larger version.

The chapel screen consists essentially of scrollwork in a continuous quatrefoil pattern, surmounted by a series of candle holders. As in other design in the building, the keynote is variety in a larger unity. Thus the scrolls spiral to centers of varying length and taper to ends of differing designs. Temporarily employed glaziers working near the spot when the screen was being placed were heard to remark that it was a shame it couldn't be made more evenly. Evidently there was not total awareness of the purposes and methods that were setting this church apart.

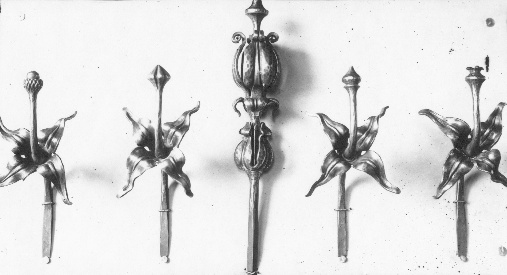

Hammered monel, delicate and individual, to grace the top of the screen that separates the chapel from the south aisle of the nave. Click on image for a larger version.

Nearby, the door leading from the vestry to the chapel combines monel framing with heavy glass in a delicate quatrefoil design. Other doors combine these materials with effects suitable to their size and position. That which leads to the tower stair on the northeast is of bullseye panes framed in a monel lattice, with rosettes relieving this pattern at top, center, and bottom of the door. Seen to better advantage is a double door, recently placed, which opens from the choir hall arcade to the north entrance of the nave. Broad and strong, these doors are of clear glass in a lovely frame of beaten monel. In certain lights, the glass of the tympanum over the door reflects the series of pointed vaults over the arcaded porch, giving a sense of depth to the entrance. On the outer side, the patina on the monel adds a note of soft green. Handles wrought in the form of a male and female bird provide the only decorative point to this door which is itself an adornment.

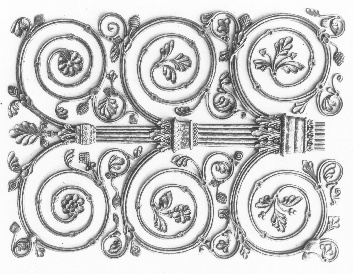

This model for a hinge designed for the west door displays a wealth of variations in leaf, flower, and berry. Yet for all the convolutions growing from its central stem, it is not restless but holds its forms in harmony. Click on image for a larger version.

Monel work appears in almost unending variety as the hardware of other doors as well; though to call by the name of "hardware" these wrought hinges, handles, studs and locks is to understate the quality of handwork. This can readily be seen on the several doors at the north end of the choir hall, beneath the Michael Tower. The monel offers a striking complement to the smooth grained finish of the teakwood, as at the porte-cochere entrance.

The east entrance to the book room under the Michael Tower is especially striking in its combination of metals. The doors of this double-leaf arch are of hammered copper sheathing formed into panels, each door a single unbroken sheet of copper. Studding the panels are bosses of varying pattern, of copper inlaid with sterling silver; and the latter touch is carried through in the silvery white handles—a ram and a ewe—in monel.

Throughout the Cathedral the locks and latches are also fashioned of monel. To open these, there is an unusual collection of monel keys, kept in a case in the book room. There are forty-seven of them, of individual and intricate design, a miniature display of the artistry and workmanship which characterize the many parts of the structure to which they provide entrance. The largest, which opens the west door, was presented in symbolic ceremony to the Bishop of the General Church by Raymond Pitcairn as donor, at the Cathedral's dedication in 1919. Photographs of these keys form the end papers of this volume.

On the west door itself are monel hinges that resulted from long and careful study, design and redesign by Edwards and Pitcairn. The study included examination in the Metropolitan Museum of New York of a model of the hinges on the great west door of Notre Dame in Paris; also the making of a plaster cast and close scrutiny of photographs of a model, from the Carnegie Museum at Pittsburgh, of a hinge from the Church of St. Giles. The hinges of the Bryn Athyn Cathedral are in design somewhere between the Romanesque of the St. Giles and the Gothic of Notre Dame. They consist of broad bands tapering in from the sides as they branch into delicate scrolls which end in various forms of Gothic leaf or flower. The design avoids both stiff conventionality and imitative naturalness; and the execution shows remarkable care in moulding of this hard metal. These hinges too are tinged with the green patina of age.

At work in the metal shop, where the utilitarian strength of steel sets off the exquisite lines of the ornamental hinge. Click on image for a larger version.

Finally, two stair railings of monel are noteworthy for a grace that unites straight lines with curves. One, on the south exterior of the church, leads to a small terrace at the vestry entrance. Set parallel to the wall of the terrace, it is of simple design, its hand-beaten rail rising to a circular curve which displays the screen pattern below in shaded light. The effect is enhanced by the stone work on which it is set, and the shrubbery nearby.

More beautiful still is the screened railing on the interior steps that lead down from the council chamber to the undercroft, in the south group. Curving in a comely line toward the viewer standing at the bottom, it has the quality of filigree against the stone behind. It has been the fitting setting for the photograph of many brides married in the Cathedral.

One last illustration of design and execution in metal is in the grilles near ground level along the south facade of the Council Hall. They are remarkable in the variety achieved without strain upon the motif of the Romanesque arch that characterizes this part of the Cathedral, a variety not easily obtained in repeated use of the round arch pattern. Here, as elsewhere in the building, the parts betoken an individuality that yet serves the harmonious whole.

Top | Previous Chapter: The Timber Work | Next Chapter: The Stained Glass | Table of Contents